Living Art, Dead Artist

Published in KUNST.EE 2014/3 Marian Kivila analyses Anonymous Boh’s (or Al Paldrok’s) solo exhibition “10 COMMANDMENTS”.

Performance art, its documentation, and the subsequent reception, use and definitions of this documentation has fascinated many art critics and historians. Performances, as ephemeral works of art, are meant to vanish from the very beginning as soon as they are conceived by the artist. The desire to preserve something impermanent often raises questions like what is the goal of documenting it, is it really necessary and whether the documentation should be considered purely as a means for documenting living art or as works of art in their own right.

As we know from art history, there are many performance artists who avoid documenting their work and also forbid their audience from doing so in any way. Their art is something rare, only meant for a small number of random viewers, and afterwards it only lives on as a fading memory in the minds of those who happened to have seen it. It seems to make sense (in a morbidly romantic way) that this is how an ephemeral work of art is born and how it dies.

Amelia Jones, a performance art theorist, has suggested that the documentation (e.g. photographs) acts as a supplement to the performance. She sees the relationship between performance and photographic documentation as co-dependent and symbiotic. Photography needs events to exist and events need photography to prove they once existed. Photography is like a key to a lost time.

There is a whole array of artists who fanatically document their performances and, from various angles, try to analyse the co-dependent relationship that Jones has described. Anonymous Boh is the kind of artist whose creative processes involving one single work of art might never be finished. He tries to find new ways to recontextualise the documentation of completed performances – sometimes as supplements, other times as independent pieces replenished with new meanings. Boh’s earlier shows have displayed photographic documentation in the way they were taken, or created settings that present reproductions of performances.

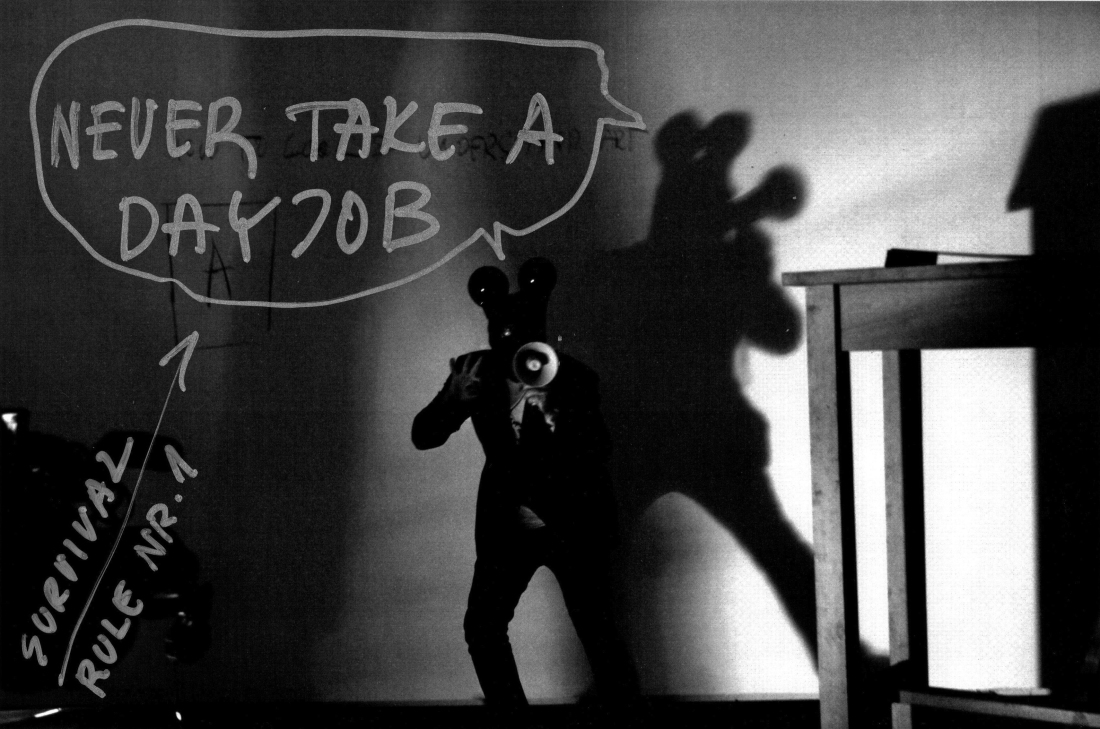

The exhibition “10 COMMANDMENTS” is based on performances by Non Grata, held in various parts of the world, and the documentation that has taken on new meanings. The scenes from past performances are placed in a new context and are reconceptualised as the time, space and audience change. That is, according to what the artist wants to say to the world.

The first commandment in the series suggests that the instructions of the former professor of Academia Non Grata are probably directed at artists to help them think independently, believe in themselves, find their talent and manage their life. If applied to a larger segment of society, the commandment “Don’t ever get employed!” would be catastrophic and would most likely lead to the destruction of that society. The commandment “Don’t consume, DIY!” refers to the potential for restructuring society according to anarchist principles – based on a natural economy, the currently prevalent wage labour would no longer be necessary.

The somewhat utopian commandments, that definitely also have a certain amount of truth in them, are a critique of artists that do not know how to use their talent. An artist working in a bar or slaving away in an ad agency has chosen the easy way out, they also believe that it is impossible to make a living as an artist. So, making this belief into a daily affirmation, they also destroy their chances of having a successful career in art.

We probably all know artists who are so busy with their day jobs that they no longer have the time to challenge the discourses of the art world, to start revolutions and keep their talent shining bright. For them, art seems to have become a mere hobby. Then again, I also know artists who successfully sell their works and because of that have acquired the rather negative label of “commercial artist”. So, Boh points to the paradox of being an artist and the need to be constantly searching for the right balance in every tiny move and thought. Boh also refers to the fact that manifests are rarely written anymore and people often conform, which he, as quite a successful and productive artist, clearly does not approve of.

As the next step we could of course muse on what an artist should be like and which expectations they should fulfil in order to be called an artist. For Boh, an artist is someone superhuman: a prophet (the commandment “If you know the truth, share it with everyone!”), an ascetic (the commandment “Escape your comfort zone!”), a philosopher (the commandment “Doubt everything!”), an extraverted and active socialiser (the commandment “Stay connected”) and an enthusiast (the commandment “Don’t complain, bring the change!), all in one person.

Boh wants the artist to be a rebel, and the artwork a loud message. Nevertheless, it seems that the best part of the exhibition is not the dominating imperatives, but the fascinating way he has presented the documentation of the performances.

I would also add a commandment for artists: “Don’t make art that screams in your face, take an enigmatic approach!” Our senses are ruined due to the over consumption of conceptual art and so we probably enjoy art more if it offers more than one possibility of interpretation and there is something to think about. There are shows that stay with you for days before you reach a cathartic understanding. Yet it is true that there have not been many exhibitions like this lately and I can agree with Boh’s criticism.

I was actually amazed by the softer side of Boh, his figurative critique. The maquette-installation “Evolution” (2014) that had lined up tin soldiers, dinosaurs and human figures according to size, finely and accurately captured the idea of escaping the comfort zone and conforming to the ideals of the welfare society.

Marian Kivila is a freelance art critic and the marketing manager at the Pärnu Museum.